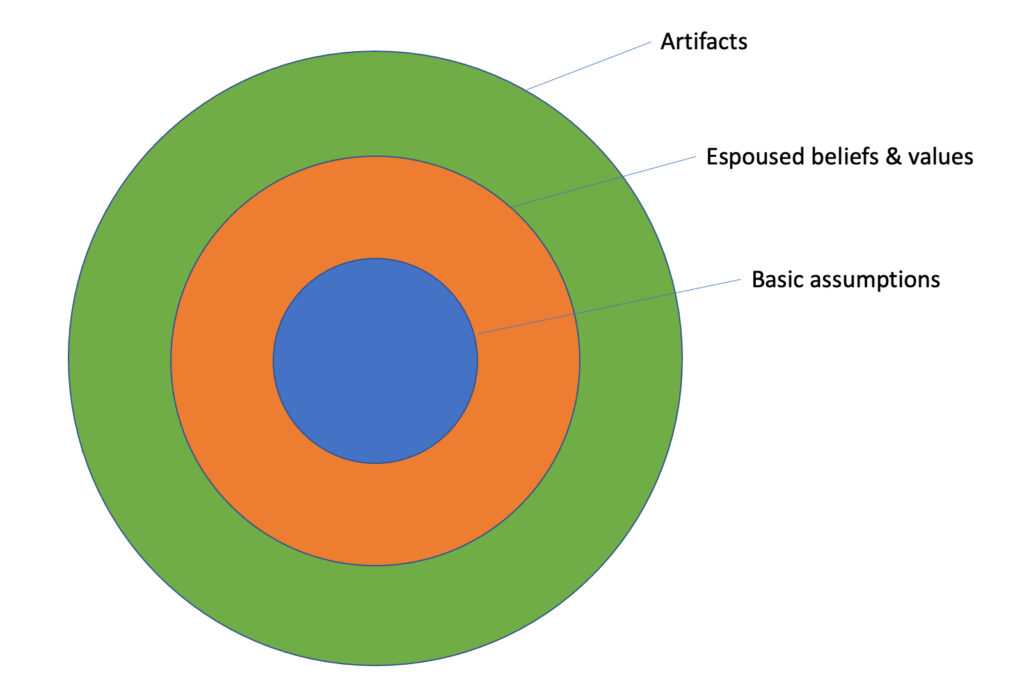

Decades ago, Sloan School of Management professor Edgar Schein developed a model for understanding and analyzing organizational culture. His model divided an organization’s culture into three levels:

- Artifacts are the things you can see–behavior, office layout, work product, etc. Artifacts are easy to see and hard to understand. The Egyptians built pyramids (artifacts). Those are easy to see. Why they built them though is harder to understand.

- Espoused beliefs & values are what you say you stand for. Values theoretically prescribe how people act.

- Basic assumptions are the foundation of culture. They are the beliefs that are so deeply embedded that most people don’t even know they are there. They are just taken for granted because essentially “this is the way the world works” or “this is just the way it is”. As long as values are not simply aspirational, they arise because of basic assumptions. Values come to be because you have encountered a certain situation enough times to eventually recognize that X or Y behavior in that situation is important to the group. Basic assumptions only appear as espoused beliefs or values when they have been recognized, but they always show up in artifacts as behavior. When that occurs, it is not always easy for outsiders to understand the behavior because they cannot see and certainly have never felt the basic assumption that led to the behavior.

Encountering culture

When you first encounter a culture, you are presented with the artifacts and have almost no ability to understand them. For example, if you visit your partner’s family for dinner for the first time and find that they fight constantly throughout the meal despite the fact you were told they are a very loving group, you likely cannot understand how fighting and being loving go together if you come from a family that perhaps did not argue through meals.

At the level of value, the idea of being a loving family sounds the same, but because of your experience, you define loving through the behavior of not arguing. The reason for this might be a basic assumption that your family has that is that you can demonstrate your love for a person by being concerned about their mental well-being in the immediate moment. Does your family ever talk about that though? Probably not. They more than likely avoid arguing because “that is just what you do” or “that is the way it is.”

This group though might have a basic assumption around love that runs more like, “You demonstrate love by focusing on the long-term outcomes.” So for example, if you’re about to make the wrong decision, I need to tell you so, and if you won’t listen, I need to make you listen. That is love in my world.

Understanding culture

In order to understand artifacts, you cannot just understand the values. You have to have enough experience with the culture to feel (if even you do not recognize) the basic assumptions.

Having moved numerous times in my life, I have encountered this many times. I would move to a new place, see someone do something that would not be a typical response where I’m from, and wonder more or less “what is with these people”. The thing is that–when you’re from a city in the west and you move to the south for example–you might find that the average person generally lacks the ability to deal with a disagreement head on and instead will just think or say to themselves “bless their heart”.

To you, it looks like they’re just avoiding conflict. When in reality, it might be that for example people in Seattle or New York or whatever other city have learned that you don’t get anywhere avoiding confrontations. And, people in Atlanta have learned that you don’t get anything out of most confrontations. They might value the same things–such as getting their jobs done or working toward a better future for their communities–but their experiences have taught them that their way of getting to those end goals is better than the alternative.

Hiring and culture

When you hire someone, they might very well align with your organization on values, and the artifacts you and they see might appear to align. For example, your company–like mine–values diversity of behavior and thought, and your candidate says, “That’s so cool. I’ve worked with some really valuable people that weren’t like everyone else in the company, but we never really got anywhere with them because our management treated everyone like a cog in a machine. So, those different people just didn’t fit in.” On the surface, all good, but once the person starts, you find that something is not working. This is where basic assumptions rear their ugly heads.

It turns out that–while your company values diversity of behavior and thought–it has an underlying assumption that it’s okay to go down a lot of unsuccessful paths on projects because those multiple failed attempts will result in arriving at the best possible outcome. Coming from the cog-and-machine environment though, your new hire might very well have learned through experience that you arrive at the best possible outcome when you limit all of the brainstorming or trying new things and instead stick to schedules and best practices. You both value diversity of behavior and thought, but your experience has led you to the conclusion that there are different times and places for those things.

Your best chance of avoiding hiring problems related to culture alignment is to ask questions that get to the candidate’s worldview. Don’t just talk about what you value or believe. Get down to why things are the way they are. Why is it better or worse to do X? Why is it better or worse to communicate in Y way? And so on.

Leadership and culture

Unlike when you are a worker, you must have an explicit understanding of basic assumptions when you are in leadership. One reason is what I’ve already said about hiring. You can align around values and beliefs, but basic assumptions dictate how those values and beliefs are acted out. Additionally, as a leader, you must have a clear understanding of your company’s basic assumptions, or else, you will struggle to understand why your people act the way they do sometimes.

As a worker, you have no need to have explicit awareness of your company’s basic assumptions. To do so would be like the difference between simply knowing that gravity acts in a certain way versus knowing why it acts in a certain way. In my example of the arguing family, most families almost never talk about arguing or not arguing. Arguing, or not, is just what they do. They have learned that that is the best way to act.

From the leader’s position though, you must get down to basic assumptions and have a clear understanding of them. Otherwise, you and someone else can seemingly agree on espoused beliefs and values, but still be in conflict that it seems is not resolvable.