Human beings are hardwired for threat detection.

Some more so than others. And, some have whatever genetic level of anxiety or neuroticism they were born with amped up by the circumstances that brought them to today. So, some people might actually be predisposed to be, let’s say, risk takers, but for all intents and purposes, what you or I see is someone who is risk averse, skittish, pick-your-particular-flavor-of-threat-detection-behavior because maybe they grew up without a stable home, were in an abusive relationship, have been attacked, or something else.

Again, at the end of the day, we all have some level of predisposition for avoiding threats, but some have that level amped up by their experiences.

Imagine a young mother 5,000 years ago needing to decide if this stranger that just walked into her village might be a threat to her child. Or, imagine that child’s young father seeing that stranger and not knowing if he can leave for the hunt that day or if he needs to stay close for protection. Some people in those circumstances decided they were safe and left to do what they needed to (hunt, farm, barter, whatever), and their child (or whatever they were protecting) was harmed. Others stayed close to home, did not get done what they needed to, and suffered due to for example their family not having food or income.

They could not predict the future. They could only place a bet. Some of them made the wrong bet by leaving, so maybe they didn’t pass on their genes because their child was murdered. And, some of them made the wrong bet by not leaving, so maybe their child starved because food was not brought home for the day when it was really needed, and again, their genes were not passed on.

Ultimately though, if your child went hungry or your household had a little less income for a single day, you stood a chance of recovering, but if your child was–let’s say–killed by that stranger, there was no recovery from that. As a result of the ability to recover being different from one choice to the next, human beings are on average more averse to threats than we are attracted to opportunity because permanence of opportunity is unreliable. The permanence of death is quite reliable though.

This is just one small contributor to the extreme attention we now pay to levels of protection that would seem odd to someone from decades or centuries past. That is not to say that for example seatbelts are unnecessary or that there is any problem with making bottles BPA free, but every potential threat piled on top of the next–no matter how small–creates a slippery slope, where we increasingly come to think of these threat avoidance measures as being necessary, and we forego potential benefits in favor of staving off threats.

You or I might think for example that it’s harmless to just walk my daughter around the corner to play at the neighbor’s when she could have just walked by herself, but society leads me to believe it’s not acceptable to just let my daughter walk alone, so I go along with that expectation despite not feeling it is necessary. It’s safer and harmless right?

But, as Todd Rose says, “Today’s collective illusions (the thing that no one believes, but goes along with, because we think everyone else believes it) become tomorrow’s norms.” And those norms just get built upon with more collective illusions, which again become norms. It’s a positive feedback loop.

We’re working our way toward a society that values protection at all costs. No risk taking. No weighing of the costs and benefits. It’s like the extreme version of Dick Cheney’s 1% doctrine. If there is any chance of threat, that’s too much.

And sadly, the media through which we increasingly engage with and understand the world amplify the collective illusions because that natural, human threat detection tendency reacts more strongly to the negative stories we encounter than the positive stories. This is why Hans Rosling said, “Good news is not news.”

All of your information (let’s call them “news”) outlets are selling something. TV and websites need visitors so that they can sell ad space. Forum and social media users are selling a viewpoint. And, so on. If they weren’t selling something, they wouldn’t care about getting your attention.

And sadly, if you’re one of those people that actually does not follow the collective illusion, if you think there are some gambles worth taking, you are now put in a position of being seen as untrustworthy because obviously you’re just not concerned about the environment or animals or children or God-knows-what. You’re too cavalier, but they (someone else) care even though you don’t. Clearly.

In today’s environment, that “compassion”, that moral high ground wins in all arguments even if it’s over-protection and comes at the cost of other benefits that could be gained, such as for example teaching my daughter within a relatively safe setting how to navigate the world alone. No, protection today over long term protection or competence in the future, right?

Within our businesses, this manifests not as an environment in which people can say and do hard things and where they can be safe to make mistakes while working toward our collective goals. Instead, this manifests as workplaces where you cannot say certain things because they make others uncomfortable, where–instead of being encouraged to do–you are mandated to no do.

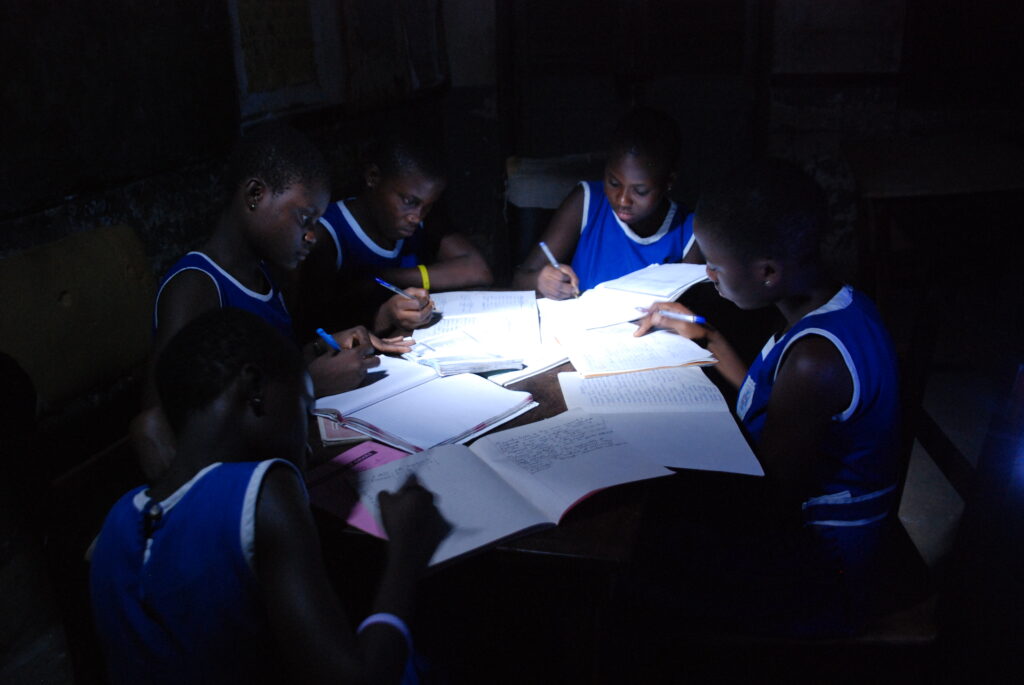

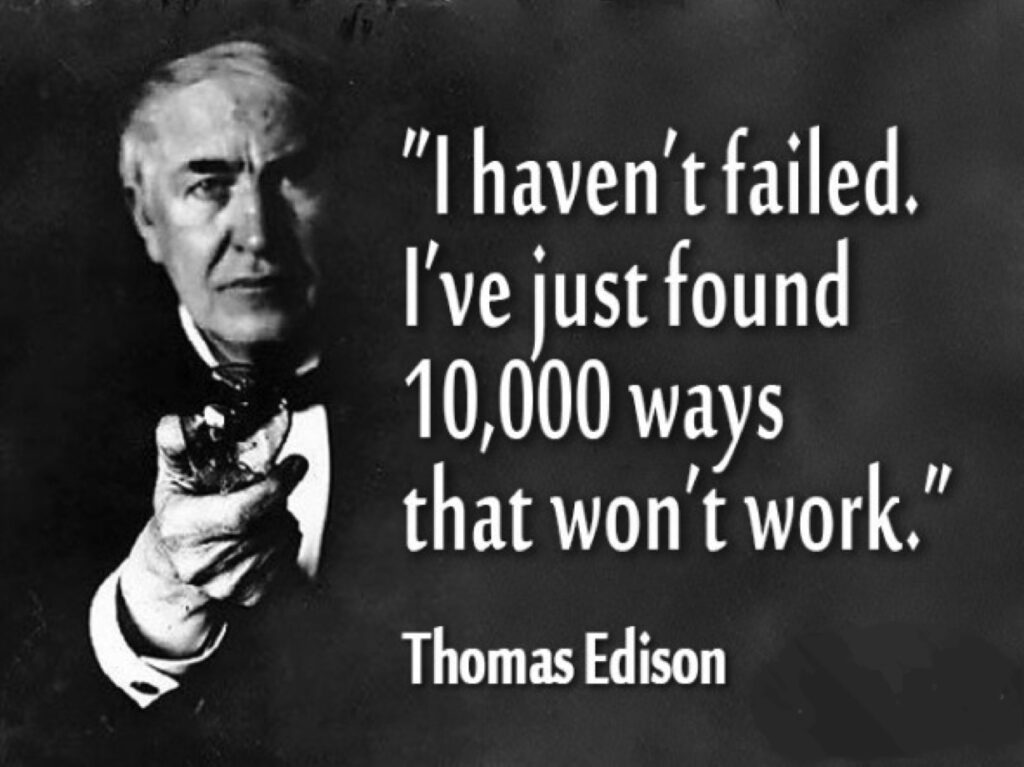

The downstream implications of this are workplaces in which most people do not feel comfortable being themselves because they have been told making the wrong joke, using the wrong phrase, looking at someone the wrong way is an unforgivable offense. So, people do not open themselves up and fully commit. Why commit when you cannot be yourself? And certainly, if I’m not committed and if I fear punishment for making mistakes, why work hard to try new things, to innovate?

At the societal level, I don’t expect this to change. This is human nature, and the machinery we have built around us support it. The structures and the collective illusions we have built within most businesses support it.

What you can do though if you question some of this security-at-all-costs is not stay silent.

If you’re silent, that makes the collective illusions even stronger and more likely to become norms for the next generation. If you at least say something though, you create the opportunity that other likeminded people can find you and that–maybe, just maybe–someone predisposed to avoid that threat starts to question the value of avoiding it over the value they could get from spending their time and energy elsewhere.

Within a business, that gives you the opportunity to build a culture in which people can be themselves, commit, find the mission and people they truly align with, and achieve something that every other organization foregoes in the interest of immediate “protection”.