I’m going to take you on a longer-than-necessary journey here, but please stick with me. It will be worthwhile.

The Industrial Revolution

Prior to the industrial revolution, nearly every business had 2 types of workers: Owners and employees. In most organizations, that was it.

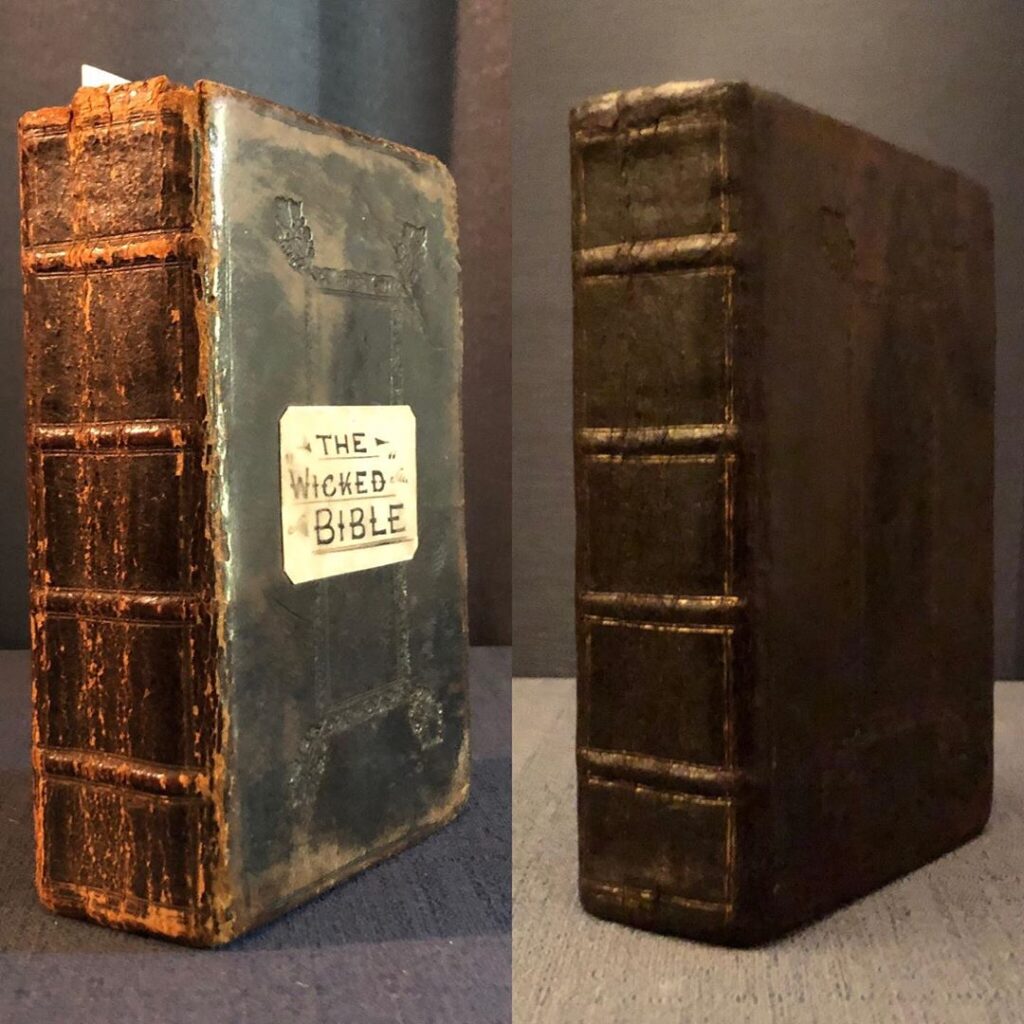

Due to most everything having to be done by hand, there was a low limit on how large a business could get. There was only so much people could work on and so much value that could be produced. Part of this restriction was due to errors. Manually performed work is inherently error prone. Think for example of the so called Wicked Bible that omitted the word Not making the commandment, “Thou shalt commit adultery.”

When work had to be performed manually, you were going to run into problems. If your work product has high error rates, people don’t want to pay a lot for fear they might get a lemon. Until the industrial revolution, this hesitation led people to not purchase things or to pay less than they otherwise might have.

Additionally, management systems simply were not developed enough for a person to be able to add value to the work of a large set of people with whom they could not immediately and frequently interact. Think of for example Scrooge and Marley’s money lending business with Scrooge sitting in the corner watching Cratchit do his job. Without the benefits of an adding machine, calculator, electric lights, a time management system, and so on, Scrooge’s ability to add value only stretched so far, which could be one of the reasons he is portrayed as such a terrible manager. He was micro-managing, being a tyrant, etc, and Cratchit’s ability to produce value was limited due to having to do everything by hand. No calculators, computers, or anything else. If this were not the case, Scrooge could have had a whole building of Cratchit’s working away, whose shoulders he did not have to look over in order to ensure that their work product was error free.

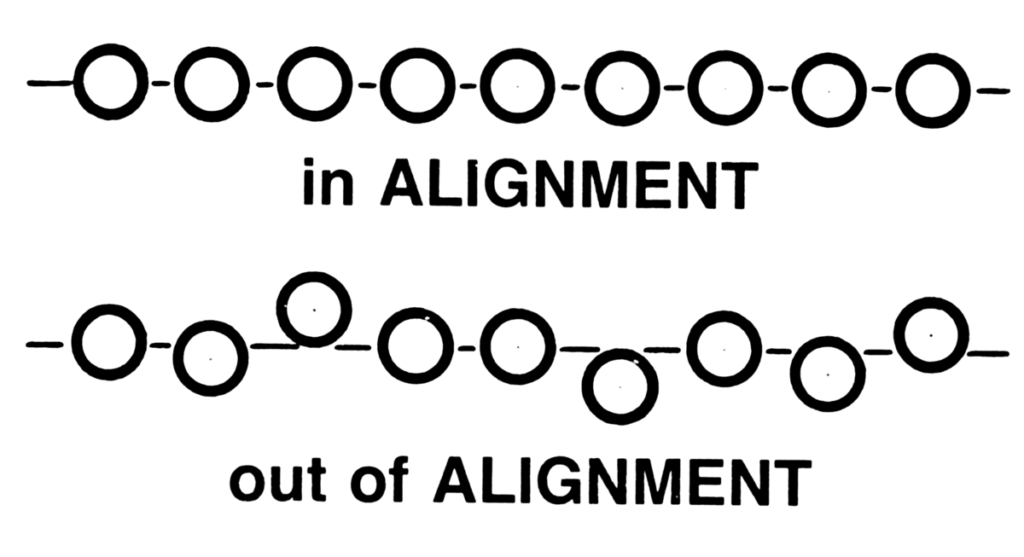

With the industrial revolution though came the ability to increase both quality and quantity of work. If I have a machine stamping the soles of shoes, I know that–once I get the machine set up correctly–it will do the job the same way every time. Humans naturally deviate. As this revolution occurred, employers were able to hire more employees to either work the machines or be treated like machines in that they only did a single task in an assembly line or division of labor scenario, which is less error prone than when a single person handles multiple tasks. At some point in this revolution and growth of the size of businesses, people like Scrooge simply did not have enough time or ability to add value to the work of all of those employees.

The widespread adoption of the assembly line greatly accelerated this shift toward more workers and less owners. Because while the assembly line–and variations of it–had been in use as far back as the Venetian Arsenal in the 12th century and even Ancient China, it was not until the industrial revolution when it began to be used to produce more than just a few items.

With the introduction of division of labor and machinery to automate work, you not only had an increase in the number of workers you could hire due to the amount of revenue you could generate, you also had higher quality products you could charge more for and specialized skillsets in your workforce that the owner-manager did not possess.

Enter the managerial class

For the first time in history, large numbers of businesses became stratified into–not a two-tier Owner-Employee organization but rather–a three-tier Owner-Manager-Employee organization. In this new structure, the owner’s responsibility was to the vision for and financial viability of the company with value adding oversight duties being shunted off to the managers. This was new and unusual, because until this time, the only people that could generally be trusted to shepherd the well-being of the company were people with an ownership stake. This new managerial class had no ownership, but still had to exercise responsibility.

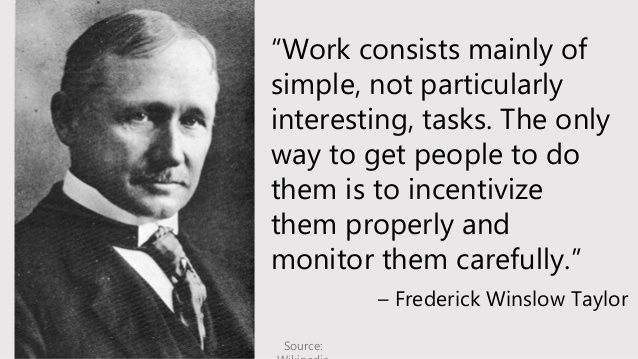

While this shift was occurring, a man by the name of Frederick Winslow Taylor revolutionized business with his 1909 book The Principles of Scientific Management, which built on a long evolution of business and efficiency thinking to espouse the viewpoint essentially that humans and their processes should be molded to machines rather than the other way around.

With the advent of scientific management came systems of control and communication that are highly efficient, but somewhat dehumanizing. All in the span of 100-200 years (less in some places), workers went from being craftspeople that knew how to do everything related to a job and who had a direct relationship with their employers and customers to people that worked on only a single piece of a job (for example only installing car fenders rather than building the whole car) and who had no relationship with their employers or customers.

I cannot find the exact quote, but in The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith said something like:

Man will become the minimum his environment requires.

Paraphrasing Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations.

And in this case, man’s environment had removed the understanding of the whole product or process and replaced it with an understanding only of installing the watch face, attaching the wiper blades, and so on, which is far more boring and less fulfilling than actually building something yourself and seeing people use it. This robbed the worker of the intellectual understanding of–and attachment to–the achievement that comes from really producing something because you never actually got to see your final product, and when you did, you had only done a small part.

As a result, it became ever more important to motivate workers externally. No longer was it just enough to do a good job because you couldn’t see the good job you had done playing out in the world. Scientific management espoused incentives and methods of control that treated employees like animals or machines. This created an environment in which management had to compel workers to work harder, better, faster even when they felt it was not worthwhile. And when their shifts were done, they were dismissed with something completely unrelated to the accomplishment of a job and instead something that fit the needs of the machine, a whistle or a bell.

Is it any wonder then that–come to today–so many people that work inside of machine-like businesses are dissatisfied with their jobs? For example, 90% of clergy express high satisfaction, while 39% of dry-cleaning workers do. Clergy own most or all of the process from beginning to end of their work and interact with their “customers”, seeing the outcomes of their efforts. Dry-cleaning workers conversely often do not interact with customers, work on a whole process from beginning to end, or see the outcomes of their efforts. The same is true of many industries and specialties.

Schools and industrialization

Many people have made the point that schools are like factories, so for the most part, I will not rehash that here. However, I will point out that–when you design a high throughput system–you cannot deal with edge cases very well. When you have an assembly line building clocks, you cannot accommodate a worker with slightly worse vision or a slower swing of the hammer. The worker fits or they don’t, and if they don’t, they are out.

The same is true of the product as well. You cannot accommodate production of a product that has variation to it. You produce the same thing over and over, and if a product has any variance, you get rid of it.

The same is true of schools. This is where so many children fall through the cracks. Whether you think of them as workers or products, if they don’t fit, they’re out.

If you have children, you’ve likely seen that they are at times well ahead or behind their peers, but generally not in everything. Rather, they might be behind in math for six months while ahead in reading, and then, it switches. If you’re a teacher though with 20, 30, or more students, it is difficult to slow down to help kids that are behind because that takes away from everyone else, and you’re on a schedule, and you have standardized tests coming up, and on and on and on. Too many demands, too many students, too little time.

If a kid is ahead, that might seem great, but instead of capitalizing on their skill or success, the teacher typically has to have them wait on everyone else. And if that student is like I was (and like a lot of kids generally are), they’re not going to sit still and just wait. They’re going to put their energy into something. This is where you might get kids that could be good at something falling out of the educational factory not because they are lazy or stupid or anything else, but because they don’t fit the mold the school requires. They have “too much energy”, “cannot focus”, etc. Much of it likely due to the fact that they are bored as a result of having to wait.

Our school system trains children to be unaccountable workers because schools are filled with children that are being pumped through the system regardless of whether they care about a specific topic, if they are ahead or behind, and more. This introduces from an early age in children resignation that they are not in school to satisfy themselves, but rather to satisfy the desire of others. Ask many children why they go to school, and a sadly, large percentage of them will say because they “have to”, “mom/dad make me”, or some variation rather than because “I get to learn” or “I enjoy it”. They go because something outside of them (people that hold power over them) tells them to do it, and once they are there, other powerholders tell them what to do.

When you’ve gone through 12 years of compulsory education, learning that what you want is less important than what some authority figure wants, you’ve received a lot of reinforcement that it’s only worth doing something when someone, who has power over you, tells you to do it. You learn to just do what others tell you to do because they hold power over you. Passion, skill, understanding, and anything else be damned.

And, no matter where you’re at in your studies, you get told to pass on to the next thing by what? The ringing of a bell or whistle just like in a factory.

What happens at work?

What we see in the work world is a lot of workers that have been habituated to only doing things that someone, who has power over them, tells them to do. Additionally, we see a lack of ownership of the duties they’re given, because honestly, it is harder to take responsibility for something that you might not be enthused about doing, but have been told to do, is it not?

Cruelly, we see some of these workers become managers and learn by example from their teachers, school administrators, and eventually managers that the way to manage people is to treat them like bigger children that should be passed through the factory system with little regard for their unique skillsets, desires, or abilities. Instead, they should be made to fit the mold of every other worker. And, if they don’t fit, they’re out of the company.

This creates an environment in too many companies in which people are there because they have to be. They need to pay the rent, college loans, and more. They’re not there because they want to be. And then while there, they’re treated like what they care about–or are good at–does not matter unless they just happen to be lucky and care about–or are good at–their jobs, or they are in a culture and/or have a boss that does not treat them like they are part of an assembly line.

The outcome of this is that too many organizations are less successful or productive than they could be. You have managers that other-ize their workforces. Believe me, I hear it all the time. “Why won’t these people just do their jobs?” or “I’ve given them everything they need, and they’re still underperforming/won’t do what I say/act like children/whatever.” You have employees that are disengaged, not looking for new or innovative solutions, and worse believe that every job is like this.

Worse still, you also have employees that are at the end of the day wiped out from doing work that does not energize or excite them. And, instead of bringing light and joy to those around them after an invigorating day of doing something they love, they instead bring their frustrations home with them.

Where it works

There are people and organizations that do not fit this mold. Some were lucky to have parents or go to schools that did not treat them like they were passing through a factory. Others did, but they found something they were passionate about and were able to succeed at that thing. Some managers actually add value rather than just bossing people around or wielding power over them. And, some companies actually have cultures that encourage people to bring some of their uniqueness to bear in the service of shared goals.

I wish it were as simple as saying that everyone should just “follow their passion”. The reality of it though, I believe, is that most of us have to work. We have bills to pay. We can avoid community groups (church, neighbors, whatever) that make us uncomfortable. We can not talk to the other folks in the gym or when we’re out walking our dogs. We can skip joining that soccer or bowling team or taking that dance class or getting that drink with some acquaintances after work. But, we generally do have to work, and it’s even part of our development that we most often want to work because work gives us the opportunity to feel productive and have our time and efforts be valued. And, work is the place where we can actually experience that the right way to do things is not to treat each other like non-humans or pieces of a machine, but rather as contributors to a greater good.

If you are a leader, you can work to establish a culture that strips away all of that factory training your staff has taken on and instead help them to realize that true motivation does not come from a powerholder telling them what to do, but rather from connecting what you are good at and care about to a shared goal and understanding that your work matters. When you do this, you’ll see more job satisfaction, more productivity, and more new and innovative solutions in place of what used to just be people taking orders.