If you would like to listen to or watch a recording of this article, you can do that here:

In today’s fast-paced, content-rich, distraction-laden world, leaders often struggle to make clear decisions under pressure. Many feel they’re constantly reacting, without ever stepping back to assess the bigger picture. But there’s an often-overlooked solution to this: mindfulness.

Why mindfulness matters for decision-making

In a world full of distractions and constant demands, it’s easy for leaders to lose focus and make reactive decisions. Our colleagues, families, and friends depend on us to make sound decisions, especially if we hold positions of power or influence. To be effective decision-makers, we must focus our attention on the most important issues.

Everyone knows what attention is. It is the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration, of consciousness are of its essence. It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others. – William James, writing in 1890

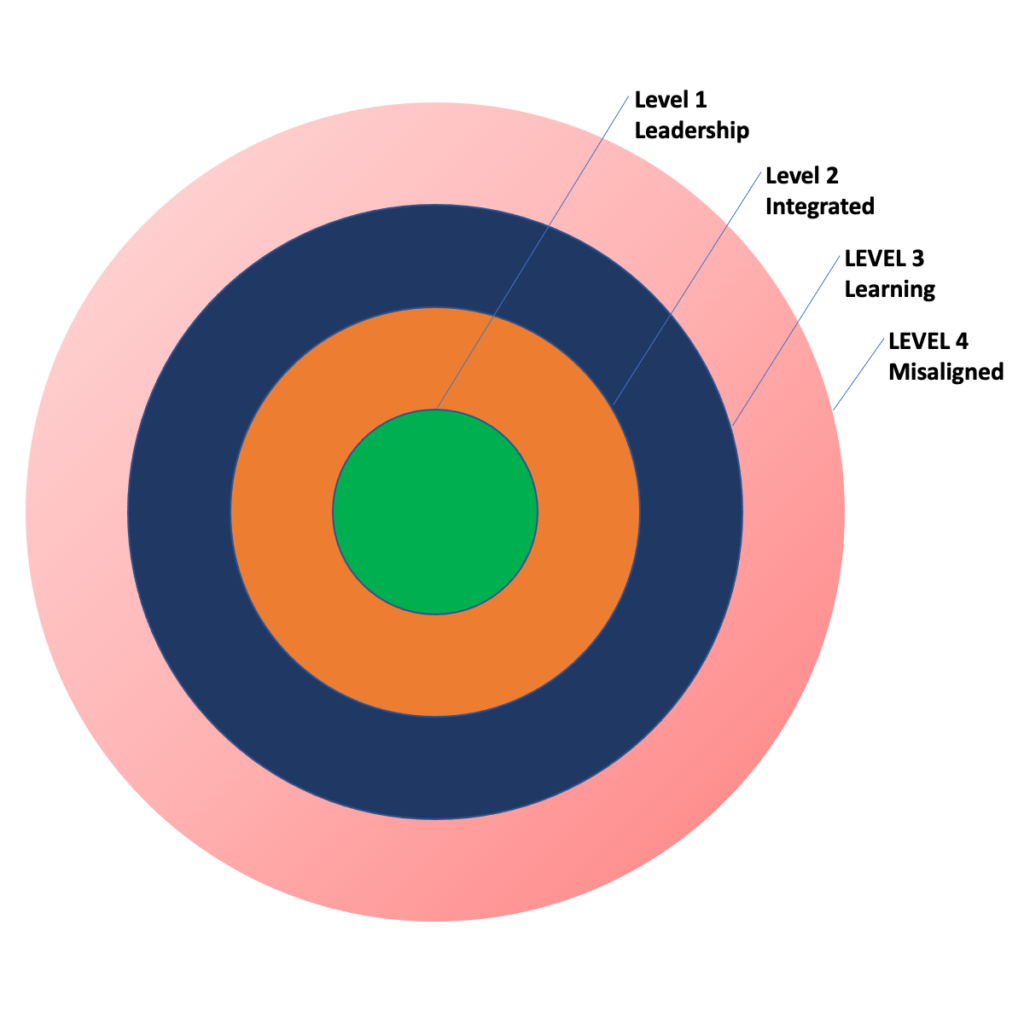

As leaders, the decisions we make shape the direction and success of our teams and organizations. Effective decision-making is critical because it impacts every aspect of our roles, from setting strategic goals to managing daily operations and responding to unexpected challenges. This need has grown with the rise of knowledge workers and the increasing role of AI in handling routine tasks. As routine tasks become automated, the value of human decision-making increases, making our ability to make sound decisions even more crucial. Many leaders face significant obstacles that hinder their decision-making abilities, such as stress, emotional reactivity, information overload, or plain old distraction. These challenges can lead to suboptimal decisions, affecting not only our performance but also the well-being of our teams.

This is where mindfulness comes in. While mindfulness is often associated with relaxation and stress reduction, its benefits extend far beyond that. Mindfulness is about being fully present and aware in the moment, thereby enhancing our ability to make clear, balanced, and informed decisions. When you are practicing mindfulness, you are not cutting out something. You are instead bringing to the forefront of your consciousness what the mind is already doing, noticing and processing innumerable things. When you are being mindful, you can more effectively choose when and what to focus on instead of being distracted and then wrapped up in one thought or feeling, one shiny object or another, one phone or computer notification, one question or appeal for attention from another person…and another and another seemingly unendingly.

| Mindlessness | Mindfulness |

| Reacting without thinking | Pausing to consider options |

| Easily distracted by thoughts | Focused on the present moment |

| Impulsive decisions | Thoughtful, intentional decisions |

| Operating on autopilot | Conscious awareness and control |

Most people are rarely mindful—in fact, many operate on autopilot. It’s similar to dreaming. Think of a time when you were dreaming: you had no control over what thought came next, and you were fully absorbed. This is how many of us go through daily life.

Mindlessness

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s research on attention shows that our ability to focus depends on factors like mental fatigue and distraction. The more tired or distracted we are, the harder it becomes to focus on anything. Mindfulness will help you make clearer, faster decisions, even in high-pressure situations. By reducing the experience of distraction, it allows you to focus on what truly matters, improving your ability to lead your team effectively and reducing costly mistakes.

A 2020 study found that the average person has over 6,000 thoughts per day—about one every 9 seconds. With so many thoughts constantly flowing through our minds, it’s no wonder that staying focused can be such a challenge. Mindfulness helps us manage this overwhelming influx by training our attention on what matters most, so we’re less likely to get swept away by the next thought that arises.

Think about yourself for a moment. How long can you truly focus on writing an email or listening to a colleague before another thought interrupts—even if just for a second? While you may maintain focus longer in some situations, as Kahneman’s research shows, attention is clearly a bigger challenge today than ever before. This constant flitting from one thought to another impacts our ability to maintain focus on tasks, which in turn affects our decision-making. When we’re not fully present for the appropriate amount of time to do a specific job, our decisions can become fragmented and less effective.

The goal of mindfulness isn’t to stop your thoughts but to become aware of them. Like the earlier metaphor of dreaming, the aim isn’t to stop the dream but to become conscious of what’s happening around you, so you’re not swept away by one thought while missing the bigger picture. By noticing when our minds wander, we can train ourselves to refocus on the task at hand, which improves our ability to make thoughtful, clear decisions.

Try this 60-second mindfulness exercise.

I’d like you to try a simple mindfulness exercise:

- Get into a comfortable position, sit up straight, and close your eyes.

- Take a slow, deep breath in and out.

- Focus your attention on your breath.

- Notice where you feel it most prominently—whether it’s at the tip of your nose, the surface of your lips, or the rise and fall of your chest or stomach.

- Set a timer, and for the next 60 seconds, try to keep your focus solely on your breath. Cover it with all your attention. While you might have thoughts about other things, gently bring your focus back to your breath whenever you notice your mind has wandered. It’s perfectly normal for thoughts to arise. The key is to recognize them and then return your attention to your breathing.

After your exercise:

How was that experience for you? Did you notice your mind wandering and then successfully bring your focus back to your breath?

This simple exercise is the foundation for sharpening your decision-making during high-stakes meetings, negotiations, or when managing competing priorities. With regular practice, you’ll find that you can stay calm, focused, and intentional even in the most difficult situations.

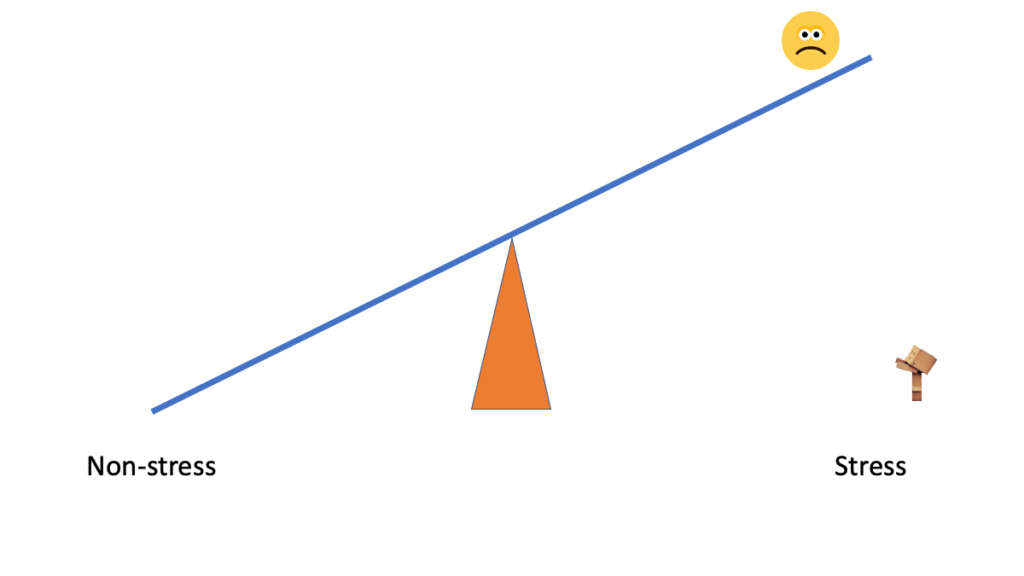

Overcoming flooding

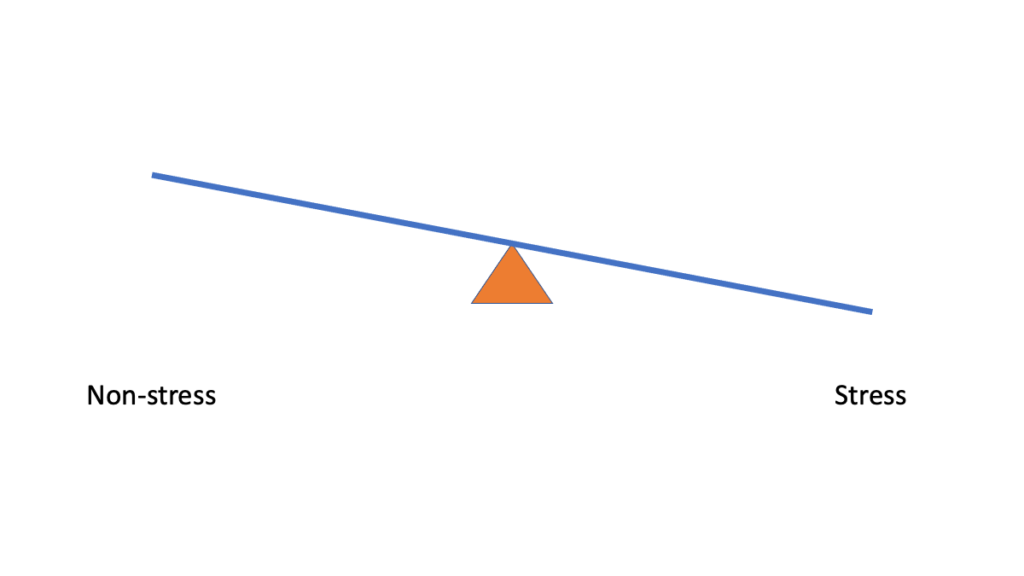

University of Washington professor John Gottman has researched what his institute calls “emotional flooding.” This happens when someone is so overwhelmed by their emotions that their decision-making skills are overpowered. Emotional flooding happens more often than you might think—it’s not just limited to heated arguments or intense grief. It can occur even in people who seem emotionally reserved.

Research from the Gottman Institute shows that pausing for just two seconds between a stimulus and a response can significantly improve performance. This applies to everything from answering simple questions to handling complex, high-stakes conversations.

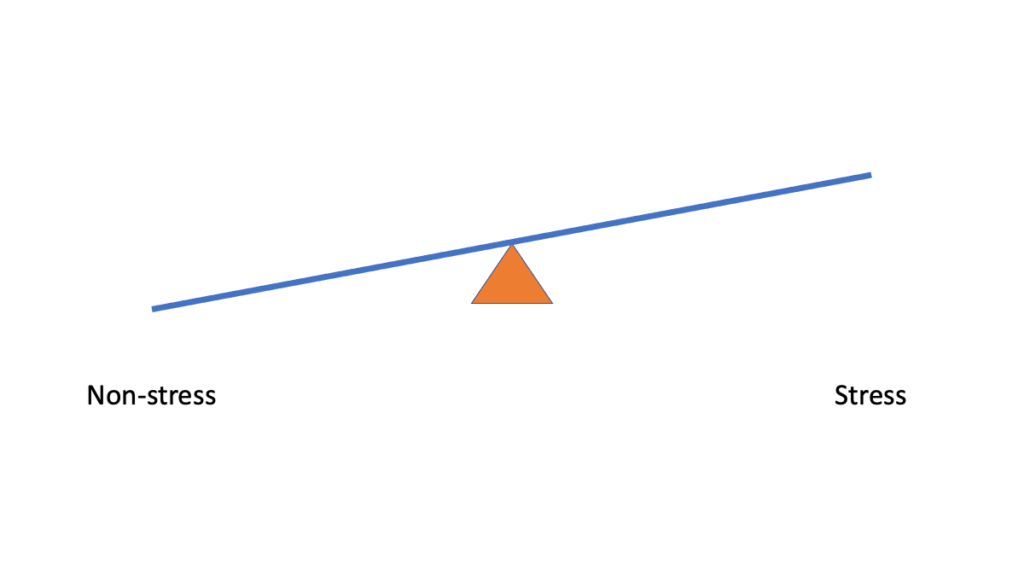

As a leader, you’re constantly required to make quick decisions, prioritize tasks, and navigate high-pressure situations. Mindfulness gives you the mental space to pause, process, and respond thoughtfully, allowing you to stay calm and clear-headed, no matter the challenges you face. When we’re mindful, we are less likely to react impulsively and more likely to provide thoughtful, well-considered responses—both qualitatively and quantitatively better.

Consider a scenario where a colleague asks you a challenging question. By pausing for a couple of seconds before responding, you give yourself the opportunity to process the question more thoroughly and provide a better, more thoughtful answer. If pausing remains at the level of a hack or trick though, you will inevitably forget about it and revert to your old, very common habits. This is why you need to practice mindfulness. So that when you have a decision to make, you do so with awareness, intention, and the ability to stay focused on the task at hand, thereby actually doing your job better.

As a leader, your ability to manage distractions and focus on what truly matters is key to success. Mindfulness helps you control your thoughts, keeping you focused on strategic priorities and reducing the risk of making reactive, impulsive decisions that can harm your team or organization. By practicing mindfulness regularly, you’ll sharpen your focus and decision-making abilities, allowing you to handle complex leadership challenges with greater ease. You’ll be able to think more strategically, make quicker decisions, and guide your team more confidently.

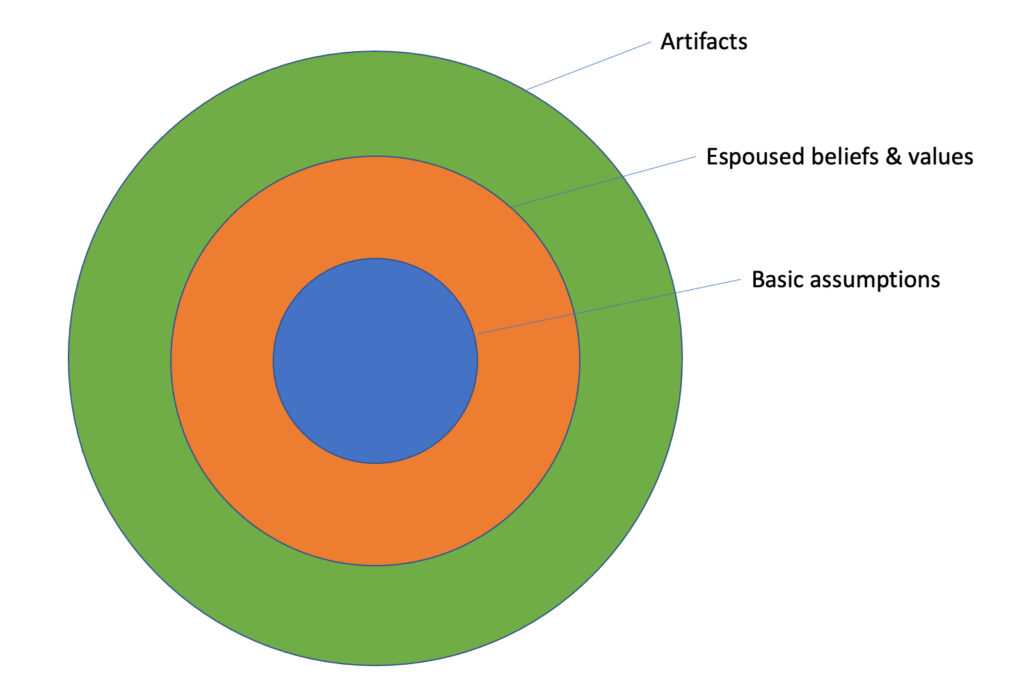

The rider and the elephant

In his book The Happiness Hypothesis, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt explains that the mind consists of two parts: the elephant (the impulsive, unconscious mind) and the rider (the rational, conscious mind). While the rider can guide the elephant, it’s only possible if the elephant allows it. When the elephant becomes scared, angry, or agitated, it takes control, leaving the rider merely along for the ride. The elephant is in control when you’re on autopilot—like when you pull into your driveway and realize you don’t remember the drive or when you impulsively yell at someone and later regret it.

Most likely, your rider was distracted and didn’t even bother to try to direct the elephant or was over-powered and simply could not direct the elephant. The elephant, your unconscious mind, just did what it believed was best, which was kept you on the road and got you to your destination. It’s the elephant that’s in command when a hockey goalie launches at the puck before ever consciously knowing or seeing where it was going, when a musician plays an incredibly fast riff on a guitar or piano, when you burn or cut your finger and are pulling your hand back almost before you even realize it. It’s the elephant that’s in control when you’re emotionally flooded, and more often, it’s the elephant that’s in control when your phone buzzes and you reflexively look at it or a colleague asks you a question and you just start speaking.

Our unconscious mind often dictates our actions and decisions, sometimes without our conscious awareness. As Haidt says in his book, to make better decisions, we need to:

- Ensure that our conscious mind is clear and focused on specific goals.

- Motivate our unconscious mind by finding emotional connections to our goals.

- Shape our environment to minimize distractions for the unconscious mind.

“You” are simply not as smart as you think you are.

It’s difficult to equate human thoughts to bits in a computer because the human brain does not function like a computer, but we can use this analogy for illustration purposes.

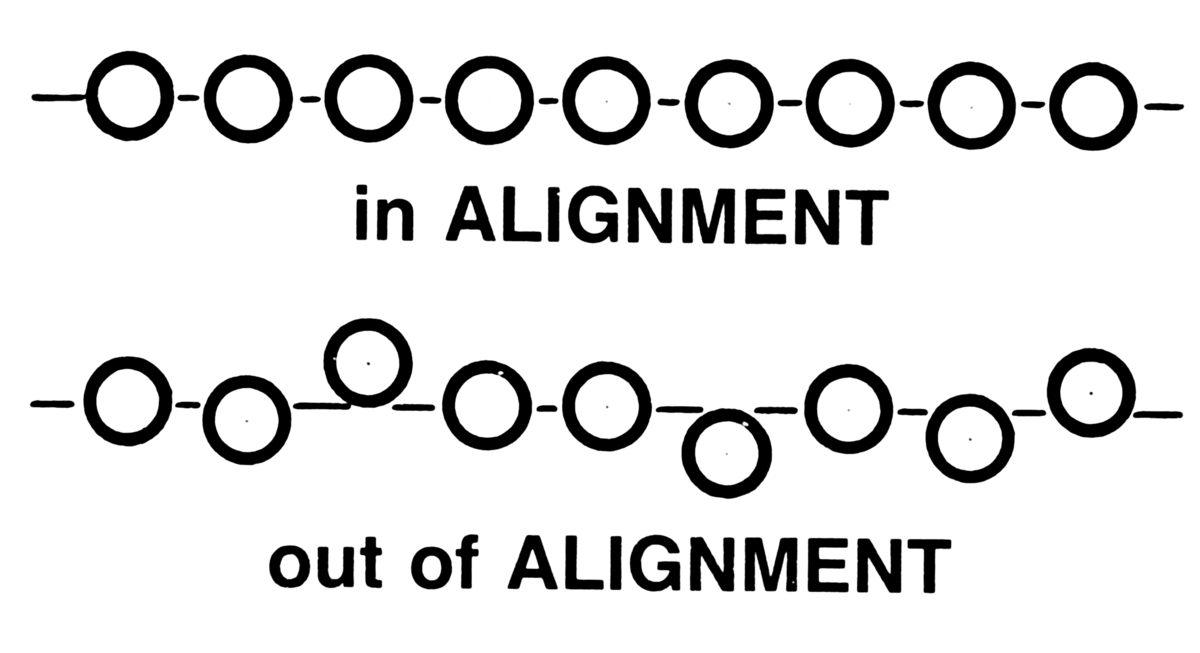

While our minds process up to 11 million bits of information per second according to some estimates, our conscious brain can handle only a fraction of that—about 50 to 400 bits (depending on who is doing the comparison and exactly how they’re making it). This gap explains why so many of our decisions happen on autopilot. Mindfulness helps bridge this divide, increasing our capacity (Kahneman) and our ability to consciously act upon our goals (Haidt).

This disparity in conscious and unconscious bandwidth means there’s a lot going on under the surface that we simply are not conscious of. We know our heart beating, much of our breathing, reaction times, and many other functions are handled unconsciously, but so is a lot of everything else that we do. You can notice this when you’re talking to someone. In most cases, the words come out of your mouth before you consciously think them. It’s almost as if it’s not you choosing the words, but you know it’s you. It’s just not the same “you” that deliberates over a decision and then makes a choice. It’s the elephant, the unconscious you that processes millions of bits of information and then decides what to say before the conscious you, the rider that only processes 50 bits per second, has time to catch up. It’s the elephant turning right or left before the rider even realizes they’ve come to a fork in the path.

Understanding how much happens in our unconscious mind—and how often we let the elephant guide our choices—helps us see why it’s so easy to go on autopilot, reacting instead of thinking. By becoming more aware of our thoughts, we can better manage our responses and make more intentional and better decisions that our colleagues need to be able to rely upon us for.

Your mind as water

I suggest you try this exercise by reading a single paragraph and following the directions before moving on to follow the directions in the next paragraph. If you are using a timer, give yourself at least a minute to test out the directions in each paragraph. If you are not using a timer, follow the directions in each paragraph for as long as you feel that you’re having to work at it, but not so long that you have a feeling of not being able to stick to it successfully anymore.

Exercise 1

Close your eyes and imagine your consciousness as a giant lake that you are looking down on from a high vantage point. This lake is vast, with no edges in sight. Everything within your view is water. This represents the space where all your thoughts and feelings arise. If you can see anything on or above the surface, you are aware of it. It’s in your consciousness. Now, we know there’s a lot below that surface as there is in any sufficiently large body of water. Sadly, we just can’t see past the surface.

Exercise 2

Now imagine a spot on the water with ripples radiating out, like when a fish breaks the surface of a still lake. These ripples represent your thoughts. Something rises from your unconscious mind, breaks the surface, and you’re suddenly aware of it. These could be thoughts about your breathing, the sounds around you, your sweaty hands, or a memory from work.

Exercise 3

As you visualize these ripples, notice how your mind jumps from one thought to another without you deciding to do so. One moment you’re picturing the lake, the next you’re thinking about an itchy foot, then suddenly you’re wondering why the neighbor is talking so loudly. Often, we get so caught up in one set of ripples that we forget about the rest of the lake—the other thoughts and ideas floating around.

If the average person has just over 6,000 thoughts per waking day and struggles to focus on a single thought for long, what often happens is similar in this visualization to zooming in and getting caught up in one set of ripples, then another, and another. This can happen in meetings, conversations, or while working on tasks, leading us to lose sight of our broader goals. One of the problems with this is that we rarely feel distracted or unable to focus. We’re simply doing what we do all the time. We’re thinking and doing. But, isn’t that also what happens while we’re dreaming? We’re certainly thinking, and as far as we experience it in the moment, we’re doing something–even if not physically. As far as we’re concerned when we are wrapped up in a dream, we are doing something, but as I’ve stated, we move from thought to thought unintentionally, effectively becoming the recipients, or victims, of whatever thoughts we receive and become wrapped up in rather than the intentional directors of our thoughts and actions.

What’s the problem with watching a TV show and having a memory pop up about high school, then focusing on the show again only to pull out our phones and google the cast, then deciding that we should check our work and personal email while we have our phones out, then checking social media only to end up doom scrolling for the next 10 minutes? We don’t notice that this aspect of our minds is such a problem because we get our tasks done–we answer that colleague’s question, we finish the email we’re writing, we sit through and participate in the meeting. What we’re rarely doing though is intentionally focusing. More often than not, what we’re actually doing is allowing ourselves to get distracted and just returning over and over and over to the same task–sending that email response to a colleague but not giving it our best thought because our mind has just come from the show we’re watching to the email and is flitting back and forth while we type for example.

The goal of mindfulness is to be aware of all these ripples on our mental lake—our thoughts and feelings—without getting caught up in them. For example, being aware of the motivation to pull out our phones or think about that old memory without being drawn in unintentionally. By being aware, by being conscious, we can choose where to direct our focus, rather than being constantly pulled from one distraction to another.

Let’s see an example of how the mind focuses

Let’s take the concepts I’ve discussed and get a more visual experience of this. For this exercise, I’ve noted in [bolded brackets] when I would spend some time on what has just been described and how much time I would put toward that.

Exercise 1

Sit or stand as if you were going to repeat one of the last exercises, but this time keep your eyes open and pointed at something simple. Don’t look at your device or anything that is moving or has intricate patterns, shapes, colors, or writing. Focus on something like a chair, a spot on the wall or the carpet in front of you, or a simple decoration. [30-ish seconds]

Exercise 2

Now, while you keep your eyes pointed there, let the focus of your attention move around your visual field to take in other things you can see. For example, if I were in my office, I might look at the carpet in front of me or the puff guard on my mic and then, keeping my eyes on that spot, consciously notice the items behind or off to the side. To give myself a better chance of really focusing my mental attention, I might then ask myself: What are those things? What are the colors and shapes? What are the objects? Keeping my eyes in the same spot, I can then shift my attention to things closer to me on my desk, such as my keyboard and some papers. [1-3 minutes]

Exercise 3

Now, if you haven’t done it already, keep your eyes in the same spot and consciously back out your mental focus. Try to just be aware of all the shapes, colors, and patterns in your visual field. You can’t visually zero in on more than one thing, but you can be aware of everything. You’re trying to not get lost in the thing you’re staring at and stop noticing everything around it in your visual field. [1-3 minutes]

Mindfulness is somewhat akin to this exercise. All of those objects are there, and if you think about it, you can take all of them in at varying levels of detail. The closer some object is to the point you’re focusing on, the more detail you get. The further out toward the periphery, the less detail your mind can pull in from your eyes.

You can point your eyes at a single thing, and even though you can tell yourself right now that you know everything else is there, that’s not generally how we experience life. When you’re at your desk typing, you’re mostly looking at one spot on the screen and maybe thinking about what your fingers are doing. You’re more than likely oblivious to all the other things in your visual field, the feeling of sitting in your chair, or anything else. You’re mentally wrapped up in that typing until a notification pops up to the side, and suddenly, your attention is pulled there, and your train of thought for your typing quickly evaporates into nothingness.

The more you practice mindfulness, the easier it will become to be aware of all the thoughts and feelings that occur to you, even though you cannot really take in more than one very deeply at any one time. When you’re in a state of mindfulness, you have a better chance to choose what to focus on rather than just reacting and getting lost in a thought.

To bring this explicitly back to decision-making, you cannot control when, for example, a colleague walks into your office or calls you on Teams. But once engaged in that conversation, you can be aware of all the thoughts and feelings popping up on the surface of your mental lake. This awareness allows you to choose to focus on the task at hand rather than letting your mind wander, which can result in lack of engagement, poor decision making, and potentially hurt feelings if the other person notices you’re not paying attention.

Pattern matching makes mindfulness hard.

Our brains are notorious resource hogs. Despite being relatively small and lightweight, they consume a significant amount of our body’s energy. This is not true for many other species because they lack or have very simple versions of many of the structures that make our brains so powerful, such as the prefrontal cortex. As humans evolved, our brain’s intense energy consumption needed to be optimized. More energy used by any part of the body means more energy must either be consumed through eating or drinking or taken from some other part of the body. And since food has often been scarce and predators common through human history, our brains having the ability to do more was great, but not if it meant that we lacked the calories needed to power that brain for the time periods needed or if that energy consumption from our brains meant that we lacked the energy to run from a predator. To conserve energy, our brains developed ways to reduce unnecessary mental effort.

This is where pattern matching comes into play. Rather than processing every detail, our brains look for familiar patterns and quickly categorize them. This conserves energy for novel or unexpected situations that might require immediate attention. In doing this, we are effectively taking what the rider could have done with its low number of bits that it can process at any one time and turning it over to the elephant that has much more processing bandwidth, but also makes decisions to for example ignore, react, or take some other action before our rider realizes that for example we didn’t pay attention to anything our colleague said in the last 5 minutes.

Imagine walking into a new conference room for the first time and seeing chairs around the table. Your rider does not spend time examining each one to see how it is unique. Instead, your elephant recognizes the pattern, a seat with four legs and a backrest, and says, “Rider, nothing to pay attention to here.” This pattern matching helps you save mental energy and conscious bandwidth so that you can focus on the things that have historically been more important, thinking about the unfamiliar things in our environment: people we do not know, objects that are foreign, sounds from the darkness around us in the forest, and so on.

However, this same mechanism can lead to issues, especially in leadership. Imagine a colleague who frequently complains but rarely takes action. You might start to pattern-match their behavior, tuning them out before you’ve gathered enough information to know if this encounter will be different. Alternatively, an employee known for being reliable might have an off day, but you might miss the signs because you’ve categorized them as always dependable. And again, why do you do this? It’s easier to let the elephant set the direction so that the rider doesn’t have to expend any more energy than necessary.

Pattern matching means saved time and energy, but also missed opportunities and bad decisions.

Pattern matching can cause us to overlook important details and make assumptions that aren’t always accurate. This can lead to missed opportunities, poor decision-making, and strained relationships within our teams. I know that we’ve all been in situations, where we’ve felt that someone wasn’t giving us their full attention, but how about this for another possible situation of pattern matching? Whether you’re male, female, black, white, straight, gay, or whatever, have you ever felt like you were getting the “All ______ people are like that” treatment?

For example, I’m an American that has lived in Germany twice and Sweden once. And, I’ve done a fair amount of traveling in my life. Even if I make allowances for some sense of insecurity or simply just misunderstanding on my part, I can tell you without a doubt that I have been pattern matched to “All Americans are like that” numerous times. In most cases, this is harmless. In some, it’s not, but regardless of whether harm is done or not, it certainly doesn’t feel good for me, and it leads those doing the pattern matching to not engage with and appreciate me in the ways that make me unique from the pattern they match me to. And yet, our brains are built to do this so that we can put our energy toward the things that we perceive as being new or novel and not the things that we think we already understand well. If “all Americans are like that” or “all women are like that” for example, I consciously or unconsciously believe I can focus on something else.

As leaders, it’s crucial to be aware of this tendency and consciously challenge our assumptions. Mindfulness can help us stay present, notice these patterns, and make more intentional decisions.

So, how do you make better decisions with mindfulness?

Next time you have a chance to make a decision, you can do something as simple as take a moment to become aware of your thoughts and feelings. You can visualize your mental lake. You can take a breath before responding. Or, you can do what I like to do, which is to ask myself, “What am I doing? (I might for example not truly be paying attention to the task in front of me.) And, what do I think about this?” This can help to break out of pattern matching. And sometimes, whatever it is that just came to mind is worth your attention, but you taking a second to ask yourself what you think about it gives you the opportunity to weigh it against everything else you have going on and say for example, “I’ll get to that later,” rather than just getting distracted by something new.

Practical uses of mindfulness for better decision making

One of the simplest metaphors for focus and decision-making is to think of the mind as a muscle. While we could talk about different mental “muscles”—like empathy or critical thinking—let’s keep it simple. Most of us struggle with focus. Our minds jump from notifications to memories, emails, grocery lists, and more, often without us realizing that we’re not giving full, uninterrupted attention to any one thing. Imagine training your ability to focus and make decisions just like you would train your body for running or weightlifting.

The simplest way to improve the strength of your mental focusing and decision-making muscles is to:

- Dedicate a small amount of time every day to practice.

- Isolate and use those muscles when appropriate.

Daily practice

What you make time for daily has the biggest impact on your life. We all make time to eat, sleep, work, talk to our families, scroll through social media, or check the news. Some of these activities help, while others harm. But what we do every day has a greater impact than, say, the weightlifting we might do once a week.

To incorporate mindfulness into your daily routine:

- Spend 10 minutes a day practicing mindfulness meditation.

- Choose a focus area—such as general mindfulness, attention to your breath, or empathy for that person you’re having a hard time appreciating right now.

- Set a quiet alarm to help you stay on track.

- Close your eyes, take deep breaths, and focus solely on your chosen intention.

I think of this as roughly equivalent to physical training. If I’m doing a general mindfulness meditation, it’s somewhat similar to doing a general workout like a walk, run, or bike. Focusing on something specific, like your breath, is similar to working a specific muscle group, like doing a back or biceps workout. Consistency and structure are just as important for training your mental muscles as they are for anything else in life.

It’s difficult to set aside time for daily practice. If you don’t exercise a muscle though, it’s much more difficult to use it well when needed. If you never walk or jog, it’s hard to sprint for the airplane as the gate is closing. If you never do pushups or pullups, it’s harder to push your kids on a swing or lift them up as much as you and they might like. The same is true of your mind. If you don’t practice mindfulness, it will be harder to focus and make the high-value and critical decisions you’re likely being paid good money to make.

Daily use

There’s no trick or hack that will work in the long run. Sure, you can follow a 5-step process or a 3-question decision tree. But the most reliable way to use mindfulness daily for better decision-making (after practicing regularly) is to recognize when mindfulness would be most especially valuable. Then, ask yourself a few simple questions or direct your mental energy toward what matters, and use those mental muscles.

Many of us have found ourselves in situations where we realize we could put down our phones and pay attention to our child or close our laptops and focus on a meeting. But switching your focus isn’t always the right move. It’s simply another set of ripples on the surface of your mental lake.

To evaluate competitors for your attention and intentionally put your focus on one, ask yourself two questions:

- “What am I doing right now?” Are you writing an email while half-heartedly nodding to your child or colleagues? Are you watching TV while doom scrolling on your phone? First, figure out where your attention is going and where it is not. For example, a colleague calls me on Teams while I’m in the middle of writing a strategy document. I greet them and engage minimally until they request a response because my mind mostly just keeps going on the task I was focused on before their call. What am I doing here? What am I paying attention to?

- “What do I think about this?” Taking a few seconds to acknowledge the new set of ripples on your mental lake can be more than enough time to simultaneously allow you to determine whether this new thing is worth devoting your attention to, if it’s worth attempting to multi-task alongside something else, or if it should be shelved for later. Often for me, this will result in me making a note to come back to whatever the new thing is. For example, I’m in the middle of a meeting, I remember I need to order something for my daughter’s birthday, and I make a digital note rather than going to order the thing, which would only take my mental focus away from the meeting for longer. This seems obvious, but honestly, how often do you think of something during a meeting and start working on that thing almost immediately?

Now, I want to say that–for the mindfulness Puritans–focusing on one thing at a time is not explicitly mindfulness. Practicing mindfulness is seeing all of those ripples on your mental lake, being aware of everything in your consciousness. For most of us, mindfulness is a means to a greater end. By practicing mindfulness, you gain the ability to focus intentionally on what matters, so you can give your full mental power to the task at hand.

Conclusion

No matter who you are—whether you’re a critical thinker, emotionally volatile, or something else—you and the people who depend on you will benefit from better decision-making. This might mean improving the quality of your decisions while increasing the speed at which you make them or being more focused and mentally present in your life.

Imagine facing a sudden crisis at work: a client is upset, the team is stressed, and decisions need to be made quickly. Instead of reacting impulsively, you take a moment to center yourself, refocus, and address the situation calmly. This mindful pause allows you to make thoughtful decisions that are best for your team and your client

In today’s fast-paced world, mastering mindfulness is not a luxury—it’s a necessity. By becoming more present and intentional in your decisions, you’ll not only improve your leadership but also experience greater clarity and calm in both your personal and professional life.

To unlock the full potential of your leadership, I encourage you to start practicing mindfulness today. Even small, daily exercises can help you make clearer, more intentional decisions and improve your focus over time.

And if you have any questions, send me an email at eric@inboundandagile.com.